This post is also available in: Deutsch (German)

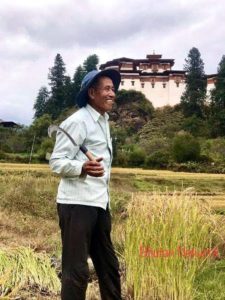

by Dorji Bidha, Drukgyel Farmers

by Dorji Bidha, Drukgyel Farmers

In the month of February, I wake up early in the mornings to check if the temperature outside is favorable to sow rice seeds. However, believe it or not, my parents and grandmother study the sky. Farmers in my village can predict the weather by simply looking closely at the blue sky above. To me it sometimes seems that when forecasting the weather the older farmers sound like fortune-tellers.

Rice – the “culinary backbone” of Bhutanese society

Our village, Phongdo, lies 2,550m above sea level. Every winter farmers therefore have a tough time preparing the plots needed to sow seeds to grow their seedlings. Winter seasons in Bhutan are harsh: dry, windy and freezing cold, with several snowfalls in January.

Fortunately, when spring is around the corner we can start preparing for yet another wonderful year. Our farmers concentrate more on rice cultivation than on any of the other cash crops (like maize, barley or wheat). Every single one of our meals includes rice, and the surplus we sell. Rice plays a vital role in our daily life, although nowadays we are advised by the Ministry of Health not to consume rice three times a day (which was the usual habit until recently).

Fortunately, when spring is around the corner we can start preparing for yet another wonderful year. Our farmers concentrate more on rice cultivation than on any of the other cash crops (like maize, barley or wheat). Every single one of our meals includes rice, and the surplus we sell. Rice plays a vital role in our daily life, although nowadays we are advised by the Ministry of Health not to consume rice three times a day (which was the usual habit until recently).

By April, the rice seeds will have started to sprout and over the next few months they will grow into seedlings for transplantation. The men of each household begin to get the paddy fields ready for plantation. Meanwhile, the women make sure that the households of the community work together because many unemployed youth have left the village. They are not interested in working on their family farms anymore.

After the rice seedlings have been transplanted in the paddy fields, we have to do weeding for several days every month. It is a very hard and tedious task. We also have to make sure that our paddy fields neither dry up nor become too wet.

It’s harvest time!

In the first week of October we prepare for the harvest season. It is believed in my village that after thruebab, the blessed rainy day, it’s best to offer our first and freshest yield, saphu, to local deities. Thruebab marks the end of monsoon and beginning of harvest time and it is a public holiday. Afterwards we begin harvesting. We start by cutting the rice plants and then dry them for a few days. Next, women thresh the rice to separate the grains from the chaff; we keep the rice straw or hay for making silage for our cows during dry season. Usually it will take a few days for each household to complete their harvest. Although still arduous and time-consuming, these days, with more modern farm equipment, our work has become much easier.

© Dorji Bidha

Another year’s work done

Once this harvesting has been done, for another entire year we don’t have to buy any rice. In fact we can exchange rice for other goods, such as butter and meat, with our friends from Lingzhi, Soe and Yaksa. Sometimes, we also go to the Sunday market to sell our rice there, saving any money made for our annual ritual expenditures.

Rice has been and will remain the “culinary backbone” of Bhutanese diet and society.

Bhutan Network sponsored over 20 sickles for the Drukgyel Farmers’ 2020 rice harvest. The sickles are “made in Bhutan” by a local black smith.